Last year, your editor was searching Congress.gov for any legislation that mentioned the Bataan Death March. I found the following celebration of the life of Cpl Walter Gann from Mississippi. Although pleased that another POW received recognition, I was soon shocked at how poorly written the insertion was as well as how full of inaccuracies it was. No one also took the time to check the proper titles for his military awards.

American POWs of Japan is a research project of Asia Policy Point, a Washington, DC-based nonprofit that studies the US policy relationship with Japan and Northeast Asia. The project aims to educate Americans on the history of the POW experience both during and after World War II and its effect on the U.S.-Japan Alliance.

Thursday, November 03, 2022

Correcting history in Congress

Last year, your editor was searching Congress.gov for any legislation that mentioned the Bataan Death March. I found the following celebration of the life of Cpl Walter Gann from Mississippi. Although pleased that another POW received recognition, I was soon shocked at how poorly written the insertion was as well as how full of inaccuracies it was. No one also took the time to check the proper titles for his military awards.

Left behind by Congress, again

An effort to honor America’s POWs leaves far too many behind

By Patrick Regan And Mindy Kotler Smith, Opinion Contributors

The Hill, 9/16/22

Today, on National POW/MIA Recognition Day, we pause to remember the suffering of all American prisoners of war.

The Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Gold Medal Act (S. 1079), now pending in Congress, seeks to award Congressional Gold Medals to some of those POWs who fought the Japanese in the early months of World War II. Credit to Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) for championing the bill and working to honor these men and women whose stories and sacrifices must not be forgotten.

But the act in its current form is insufficient.

As written, it would honor only those who served on Bataan and Corregidor in the Philippines. It leaves out Americans who also tried with no hope of resupply and antiquated weapons to stave off Japan’s lightning advance through Southeast Asia from Aug. 8, 1941, to June 10, 1942 — in Midway, Wake Island, Guam, Java, all of the Philippine Islands, the Aleutians and at sea.

These are the Americans who President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in August 1943, when the outcome of WWII was still uncertain, “will be remembered so long as men continue to respect bravery, devotion, and determination.” This still holds true.

The Philippines is often central to the most-common stories of American POW suffering and survival, in part because that is where so many endured the infamous Bataan Death March. The Americans there held out for months in 1942 on the Bataan peninsula of Luzon and finally at the tiny fortress islands in Manila Bay, the best known being Corregidor, until they could no longer hold off the resupplied Japanese.

But the stories of survival and subsequent Japanese brutality are no less remarkable in other parts of the Philippines or the Pacific theater.

The few hundred Marines and Navy sailors left to defend Guam were overrun by the Japanese in a matter of days by Dec. 10, 1941. Guam was the first American territory to be occupied by the Japanese during the war. The battle’s survivors would endure nearly the entire war as prisoners of the enemy.

At Wake Island, more than 400 Marines, 1,200 unarmed civilians and 45 Chamorro Pan Am airline employees heroically held off a Japanese armada for an unheard of nearly two weeks from Dec. 8-Dec 23, 1941. Marine Corps aviator Maj. Henry T. Elrod —aka Hammerin’ Hank — was the first U.S. pilot to sink a warship from a fighter plane. Elrod was killed on the last day of the battle and was the first aviator to receive the Medal of Honor in World War II.

Hundreds of miles south of the Indonesian island Java, on March 1, 1942, the USS Edsall’s skipper, Lt. Joshua Nix of Memphis, Tenn., laid down smokescreens and followed a series of evasive maneuvers that so frustrated four Japanese warships that air support had to be called to sink her. It took two ferocious hours of combat to end the Edsall. A small number of the 187 men on board were rescued. Their beheaded bodies were discovered in a mass grave in Celebes after the war.

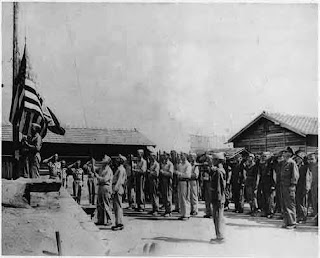

Seventy-seven years ago this month, American rescue teams liberated American and Allied POWs scattered throughout Japan’s 775 POW camps across the Pacific. In Japan, one of those was Hirohata Camp 12-B, south of Osaka. Hirohata housed 300 Americans, one Australian and one Englishman. The men were survivors from Guam, Wake Island, all over the Philippines, USS Yorktown and USS Penguin.

When word came to camp in late August that the war was over, Marine gunner Earl B. Ercanbrack gathered the Americans in the courtyard of the camp, where for the previous two years they had counted off in Japanese every morning before going off to backbreaking slave labor in a Nippon Steel mill and on its dock. The civilian overseers treated them as criminals and subjected them to ridicule and cruel, capricious punishments.

According to what Ercanbrack later told his hometown newspaper, The Monitor in McAllen, Texas, he ordered the camp’s guards to remove the Japanese flag from the 75-foot pole in the courtyard. It was replaced by an American flag hastily sewn together using a white parachute, red curtain and two blue Japanese shirts.

As the makeshift American flag rose over the camp, someone started singing “God Bless America.” Others joined in, until 300 American POWs — finally free — crescendoed in unison with the song’s final line: “God bless America, my home sweet home.”

Think about those 300 men — tortured, starved and ordered to work as slave labor for years — proudly uniting to sing “God Bless America.” Now imagine awarding Congressional Gold Medals to only those in that 300 who had served in Bataan and Corregidor.

It would be wise for Congress to follow the Hirohata prisoners’ example of unity and revise the bill to award a Congressional Gold Medal to all Americans who participated in those first desperate battles of WWII in the Pacific.

Ercanbrack, who fought and was captured at Guam and organized the U.S. flag raising in the Hirohata camp, would not be eligible for the Gold Medal now under consideration. That’s just not good enough.

Patrick Regan and Mindy Kotler Smith are members of the American Defenders of Bataan and the Corregidor Memorial Society and are descendants of men who fought in The Philippines. Regan’s grandfather, U.S. Army Air Corps SSgt Donald Regan, survived the Bataan Death March and Nippon Steel’s Hirohata POW camp in Japan.