Last year, your editor was searching Congress.gov for any legislation that mentioned the Bataan Death March. I found the following celebration of the life of Cpl Walter Gann from Mississippi. Although pleased that another POW received recognition, I was soon shocked at how poorly written the insertion was as well as how full of inaccuracies it was. No one also took the time to check the proper titles for his military awards.

American POWs of Japan is a research project of Asia Policy Point, a Washington, DC-based nonprofit that studies the US policy relationship with Japan and Northeast Asia. The project aims to educate Americans on the history of the POW experience both during and after World War II and its effect on the U.S.-Japan Alliance.

Thursday, November 03, 2022

Correcting history in Congress

Last year, your editor was searching Congress.gov for any legislation that mentioned the Bataan Death March. I found the following celebration of the life of Cpl Walter Gann from Mississippi. Although pleased that another POW received recognition, I was soon shocked at how poorly written the insertion was as well as how full of inaccuracies it was. No one also took the time to check the proper titles for his military awards.

Left behind by Congress, again

An effort to honor America’s POWs leaves far too many behind

By Patrick Regan And Mindy Kotler Smith, Opinion Contributors

The Hill, 9/16/22

Today, on National POW/MIA Recognition Day, we pause to remember the suffering of all American prisoners of war.

The Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Gold Medal Act (S. 1079), now pending in Congress, seeks to award Congressional Gold Medals to some of those POWs who fought the Japanese in the early months of World War II. Credit to Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) for championing the bill and working to honor these men and women whose stories and sacrifices must not be forgotten.

But the act in its current form is insufficient.

As written, it would honor only those who served on Bataan and Corregidor in the Philippines. It leaves out Americans who also tried with no hope of resupply and antiquated weapons to stave off Japan’s lightning advance through Southeast Asia from Aug. 8, 1941, to June 10, 1942 — in Midway, Wake Island, Guam, Java, all of the Philippine Islands, the Aleutians and at sea.

These are the Americans who President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in August 1943, when the outcome of WWII was still uncertain, “will be remembered so long as men continue to respect bravery, devotion, and determination.” This still holds true.

The Philippines is often central to the most-common stories of American POW suffering and survival, in part because that is where so many endured the infamous Bataan Death March. The Americans there held out for months in 1942 on the Bataan peninsula of Luzon and finally at the tiny fortress islands in Manila Bay, the best known being Corregidor, until they could no longer hold off the resupplied Japanese.

But the stories of survival and subsequent Japanese brutality are no less remarkable in other parts of the Philippines or the Pacific theater.

The few hundred Marines and Navy sailors left to defend Guam were overrun by the Japanese in a matter of days by Dec. 10, 1941. Guam was the first American territory to be occupied by the Japanese during the war. The battle’s survivors would endure nearly the entire war as prisoners of the enemy.

At Wake Island, more than 400 Marines, 1,200 unarmed civilians and 45 Chamorro Pan Am airline employees heroically held off a Japanese armada for an unheard of nearly two weeks from Dec. 8-Dec 23, 1941. Marine Corps aviator Maj. Henry T. Elrod —aka Hammerin’ Hank — was the first U.S. pilot to sink a warship from a fighter plane. Elrod was killed on the last day of the battle and was the first aviator to receive the Medal of Honor in World War II.

Hundreds of miles south of the Indonesian island Java, on March 1, 1942, the USS Edsall’s skipper, Lt. Joshua Nix of Memphis, Tenn., laid down smokescreens and followed a series of evasive maneuvers that so frustrated four Japanese warships that air support had to be called to sink her. It took two ferocious hours of combat to end the Edsall. A small number of the 187 men on board were rescued. Their beheaded bodies were discovered in a mass grave in Celebes after the war.

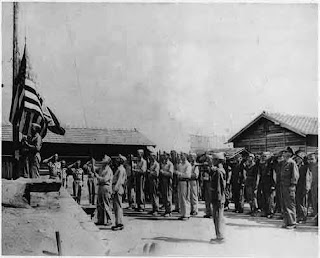

Seventy-seven years ago this month, American rescue teams liberated American and Allied POWs scattered throughout Japan’s 775 POW camps across the Pacific. In Japan, one of those was Hirohata Camp 12-B, south of Osaka. Hirohata housed 300 Americans, one Australian and one Englishman. The men were survivors from Guam, Wake Island, all over the Philippines, USS Yorktown and USS Penguin.

When word came to camp in late August that the war was over, Marine gunner Earl B. Ercanbrack gathered the Americans in the courtyard of the camp, where for the previous two years they had counted off in Japanese every morning before going off to backbreaking slave labor in a Nippon Steel mill and on its dock. The civilian overseers treated them as criminals and subjected them to ridicule and cruel, capricious punishments.

According to what Ercanbrack later told his hometown newspaper, The Monitor in McAllen, Texas, he ordered the camp’s guards to remove the Japanese flag from the 75-foot pole in the courtyard. It was replaced by an American flag hastily sewn together using a white parachute, red curtain and two blue Japanese shirts.

As the makeshift American flag rose over the camp, someone started singing “God Bless America.” Others joined in, until 300 American POWs — finally free — crescendoed in unison with the song’s final line: “God bless America, my home sweet home.”

Think about those 300 men — tortured, starved and ordered to work as slave labor for years — proudly uniting to sing “God Bless America.” Now imagine awarding Congressional Gold Medals to only those in that 300 who had served in Bataan and Corregidor.

It would be wise for Congress to follow the Hirohata prisoners’ example of unity and revise the bill to award a Congressional Gold Medal to all Americans who participated in those first desperate battles of WWII in the Pacific.

Ercanbrack, who fought and was captured at Guam and organized the U.S. flag raising in the Hirohata camp, would not be eligible for the Gold Medal now under consideration. That’s just not good enough.

Patrick Regan and Mindy Kotler Smith are members of the American Defenders of Bataan and the Corregidor Memorial Society and are descendants of men who fought in The Philippines. Regan’s grandfather, U.S. Army Air Corps SSgt Donald Regan, survived the Bataan Death March and Nippon Steel’s Hirohata POW camp in Japan.

Thursday, September 08, 2022

Upcoming events of interest to the POW community

WAR CRIMES - AN ANALYSIS OF CAUSES & METHODOLOGY FROM WWII IN THE PHILIPPINES TO TODAY. 9/15, 5:30 -7:00pm (PDT), WEBINAR. Sponsor: Bataan Legacy Historical Society. Speakers: Cecilia Gaerlan, Founder & Executive Director of Bataan Legacy Historical Society; Mark Hull is a full professor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, KS.

THE AMERICAN POW EXPERIENCE AND THE MIA LEGACY. 9/16, 2:30-3:30pm (EDT), VIRTUAL. Sponsor: Virginia War Memorial Assistant. Speaker: Virginia War Memorial Assistant Director of Education Crystal Coon.

1942: THE PERILOUS YEAR. Explores how that year was truly the hinge point of all of WWII. 9/16-17, IN PERSON OR VIRTUALLY. Sponsor: The Admiral Nimitz Foundation, National Museum of the Pacific War, Fredericksburg, Texas. Speakers: Richard B. Frank is an internationally recognized leading authority on the Asia-Pacific War, author of many books on the Pacific War, most recently Tower of Skulls (2020); Craig L. Symonds is a professor of history emeritus at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, where he taught for thirty years and served as History Department Chair; Jonathan Parshall is an independent WWII scholar. He is co-author of Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway, which is widely acclaimed as the definitive account of that crucial battle; John C. McManus is Curators’ Distinguished Professor of U.S. military history at the Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T); Katherine Sharp Landdeck is an associate professor of history at Texas Woman’s University, the home of the WASP archives. FEE.

WORLDMAKING IN THE LONG GREAT WAR. 9/19, 4:00-5:30pm (EDT), WEBINAR. Sponsor: Yale Alumni Academy. Speaker: author, Jonathan Wyrtzen, Associate Professor of Sociology and History , Yale University. PURCHASE BOOK: https://amzn.to/3Kt0cn9

12TH ANNUAL AMERICAN DEFENDERS OF BATAAN AND CORREGIDOR MEMORIAL SOCIETY CONVENTION. 9/21-24, IN PERSON. Location: DoubleTree by Hilton Seattle Airport, Washington. Speakers include: Author Jody Beck: Your Loving Son Ty: A World War II Story of Hope and Horror in the Pacific; Ralph Longway, Civilian Internee of Imperial Japan during WWII; Sandra Harding: A daughter's story of the personal journeys of an Army nurse and an Army Infantry Officer, their chance meeting on Corregidor and passage from paradise and freedom to internment by the Japanese; Mark Kelso: MIA Cold Case: the story of Lt. Hyman Victor Sherman; 2019 Japanese/American Friendship Visitation Program participants report.

FROM STEWARDS TO FLAG OFFICERS: FILIPINOS IN THE U.S. NAVY. 10/19, Noon-1:30pm (EDT), IN PERSON ONLY. Sponsor: National Museum of the United States Navy and Bataan Legacy Historical Society. Speakers: Luisito Maligat, Management and Program Analyst, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); Lorna Mae Devera, Customer Advocacy Manager, Leidos; Paula Hackbart, President, Filipino American Midshipman Club, U.S. Naval Academy; Moderator: Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox, SES, USN (Retired), Director, Naval History and Heritage Command, Curator of the Navy, Washington, DC.

Sunday, September 04, 2022

The true meaning of VJ Day

The Bravery of Americaʼs World War II Pacific Heroes Must Not Be Forgotten The Bravery of America’s World War II Pacific Heroes Must Not Be Forgotten

Percival taking pen from MacArthur.

It appears that Wainwright is without his cane.

It must have been very difficult for him.

National Interest, September 2, 2022

by Mindy L. Kotler, Asia Policy Point

As Congress returns to work next week, it has an opportunity to complete a vital but long-pending project: the awarding of the Congressional Gold Medal to all the American men and women engaged in the early defensive battles against Imperial Japan. For too long their sacrifice has been ignored or merely distilled to the horrific Bataan Death March. This is an enormous simplification that does a disservice to all who did the extraordinary with all the odds against them.

Seventy-seven years ago today, on September 2, 1945, when aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces Army General Douglas MacArthur signed the Instrument of Surrender, which accepted Imperial Japan’s defeat in World War II. With over 300 ships in the Bay and nearly 800 planes in the air, the Allies’ total might was on display.

Before signing, he called for British general Arthur E. Percival and American general Jonathan M. Wainwright to join him. The two had respectively presided over the historic surrenders by the Allies in Singapore and the Philippines in 1942. They stood behind him as he signed the document five times. MacArthur then waved to Wainwright to come forward and accept one of the pens. He handed a second pen to Percival.

Few now understand the importance of that dramatic gesture. Both Percival and Wainwright had commanded the desperate, early, but unsuccessful defensive battles in the Pacific. In 1942, Japan looked invincible as its troops swept through and occupied Southeast Asia. Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, Hawaii; Darwin, Australia; and even Ellwood, California, with impunity.

Percival and Wainwright suffered the humiliation of the greatest military defeats in their nation’s history followed by years as prisoners of war of the Japanese. Yet the men and women who fought under them had displayed uncommon heroism, resourcefulness, and tenacity. Whereas they did not nor could not then slow the Japanese advance, they were, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt told Wainwright on the morning of the fall of Corregidor, the “shining example of patriotic fortitude and self-sacrifice” that would be the “guarantee of victory.”

Wainwright, skeletal, white-haired, and leaning on a cane [apparently not during the ceremony], had been liberated, together with Percival, from a Japanese prison camp in Manchuria just days before the ceremony. On the deck of the Missouri, he stood as a visitant representing all the Americans who first engaged the enemy in the Pacific. These men and women acted with extraordinary valor in efforts to stop Japan’s advance with antiquated weapons, too few troops, and no prospect of resupply.

And it is these men and women who have earned a gold medal. We often forget that hours after the attacks on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Imperial Japanese forces launched coordinated attacks throughout Asia, striking military facilities from Thailand to the Commonwealth of the Philippines. Within days the British and American Pacific-based fleets and air forces were decimated. For the first six months of World War II after the U.S. entry into the war, the Japanese had full control over the air and sea in the Western Pacific. Our troops nevertheless resisted until they had exhausted their resources.

In the Philippines, on December 8, 1941, the “first to fire” at the Japanese invaders were the New Mexico National Guardsmen from the 200th and 515th Coast Artillery (AA) regiments— successors to the famed “Rough Riders” of the Spanish-American War. Assigned to defend Clark Field north of Manila, they found that none of their artillery was capable of reaching the high-flying Japanese planes.

Alongside them was the Provisional Tank Group. National Guardsmen from seven states who had arrived in the Philippines barely a week before the outbreak of war. On that first day, Pvt. Robert H. Brooks, an African American member of Harrodsburg, Kentucky’s Company D, 192nd Tank Battalion became the first member of the Armored Force to die in WWII. He was honored with having the parade field at Fort Knox named after him. At the same time, TSGT Temon “Bud” Bardowski of Maywood, Illinois’s Company B, 192nd Tank Battalion, is credited with bringing down the first enemy plane by a U.S. armored unit in World War II.

At Midway in the first days of the war, First Lieutenant George H. Cannon from Michigan received for “extraordinary courage and disregard of his own condition” the first Medal of Honor to a U.S. Marine in World War II. Although mortally wounded by enemy shellfire, he refused to be relieved until all his men were evacuated, and he had reorganized his command post. On Wake Island, 400 U.S. Marines, 1,200 unarmed civilian contractors, and forty-five Chamorro Pan American Airways employees fought off a Japanese armada for nearly two weeks. Marine Corps aviator Maj. Henry T. Elrod fought valiantly and was the first U.S. pilot to sink a warship from a fighter plane. The Georgian, who was killed on the last day of the battle, received a Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry.”

Action at sea was equally valorous. The U.S. Asiatic Fleet was destroyed with the March 1, 1942, sinking of the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) in the Sunda Strait. The ship’s captain, Albert Harold Rooks from Washington State, who went down with his ship, received the Navy’s first Medal of Honor for “extraordinary heroism.” Most of the ship’s 300 survivors ended up as slave laborers on the Thai-Burma Death Railway.

Not far from the USS Houston, the Japanese sunk the destroyer USS Pope (DD-225). The ship’s wounded executive officer, Lt Richard Nott Antrim, kept his surviving crew together until rescue three days later by the Japanese. But it was for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity” in a Japanese POW camp on Celebes one month later that the Indiana native received the Medal of Honor for saving a fellow POW from a savage beating by stepping forward and offering to take the rest of the punishment.

On the Philippine Islands, in contrast to other Allied encounters with Japan at the time, U.S. Armed Forces under the command of the United States Army Forces Far East (USAFFE) fought a prolonged six-month resistance to invasion. The defense of the Philippines even included, on January 16, 1942, the last cavalry charge in American military history. Led by Lieutenant Edwin P. Ramsey, the action so surprised the Japanese that they broke and ran. After the fall of Bataan, Ramsey became a legendary guerilla leader in the Philippines.

Anticipating the fall of Corregidor and all the Philippines, Roosevelt took the day before the emperor’s birthday, April 28, 1942, to give a fireside talk, "On Sacrifice." He used the battles in the Pacific to inspire and energize the American people. He first recounted the exploits of the U.S. Navy’s chief medical officer at Surabaya, Java, Lt. Cmdr. Corydon McAlmont Wassell from Arkansas. Wassell had evacuated from Java eleven severely wounded sailors from the USS Houston and the USS Marblehead (CL-12) “almost like a Christ-like shepherd devoted to his flock” to Australia as the island fell to Japan.

The president ended his talk by recognizing Texan Lt. Hewett T. “Shorty” Wheless, a B-17D Flying Fortress pilot in the Philippines. On December 14, 1941, he maneuvered his severely damaged plane to not only deliver its payload on a Japanese convoy, but also to shoot down six Zero fighters and to land his aircraft riddled with 1,600 bullets on a blocked runway with no landing gear, two engines out, and nearly all his control cables gone. Roosevelt told the American public that this and other extraordinary tales of bravery should not be considered “exceptional.” Instead, he concluded that “they are typical examples of individual heroism and skill” that American had been demonstrating.

And maybe during this time the bravest of all was Alaska school teacher Etta Jones. She was sixty-two when the Japanese invaded the Aleutian island of Attu. On June 7, 1942, they captured her, her weatherman husband, Charles Foster Jones, and the entire population of forty-two Unangax̂ (Aleut). Charles was executed, after which she was forced to watch a Japanese officer behead his corpse. The Native Americans and she were taken to Japan as prisoners of war.

Most Americans, if they think of the early months of the war in the Pacific, highlight the Bataan Death March. This 100-mile, three-part trek north up the Bataan Peninsula west of Manila embodied all the disappointment, failure, and humiliation of the war. The forced march was marked by the Japanese capturers’ conscious cruelty in withholding food, water, and medicine; in looting and murder; and in inflicting capricious abuse and torture upon defenseless prisoners. Thousands died.

Forgotten are the four months of combat prowess, dedication, and pure heroism by the American and Filipino troops on Bataan. An estimated 12,000 American troops, 76,000 Filipino troops, and 20,000 Filipino civilians endured siege conditions marked by hunger, disease, and confusion with dwindling and antiquated war materiel. Their commanding general, Edward B. King understood his seriously degraded force could not continue and surrendered the peninsula on April 9, 1942.

As thousands escaped the peninsula or were in field hospitals, it is uncertain how many people were on the march that started that same day. Those who did not flee were rounded up at the tip of Bataan and other locations along the peninsula for a sixty-five-mile merciless march in the tropical sun northward to a train station at San Fernando. There they were packed standing into small unventilated boxcars for the twenty-four-mile journey to Capas. Many died standing. The survivors made a final six-mile march to Camp O’Donnell, a makeshift POW camp with only one source of water. Thousands more died there of disease, starvation, and lack of medical care.

Yet it took two more months for the Japanese to subdue all the Philippines. General Masaharu Homma did not accept General Wainwright’s May 6th surrender of Corregidor and the other fortress islands in Manila Bay. Instead, he kept the men and women there as hostages until he received assurance on June 9, 1942, that all the USAFFE troops throughout the Philippines had surrendered. General Guy Fort, commander of the Lanao Force of the 81st Philippine Division in Mindanao, was one of the last to surrender. His refusal to betray his troops who had become guerillas earned him the Mindanao Death March and eventually a firing squad. He is the only American-born general to have been executed by the enemy.

In January 1946, 200 former POWs of Japan recuperating in the Fort Devens hospital formed the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor. Notwithstanding their name, the organization was formed to memorialize the spirit of perseverance, faith, and optimism of

...all American citizens - men and women who served at any time in the Armed Forces of the United States in the defense of the Philippine Islands between December 7, 1941 and May 10, 1942 inclusive and any man or woman who may have been attached to any unit of force of the Asiatic Fleet, Philippine Archipelago, Wake Island, Marianna Islands, Midway Island and Dutch East Indies.

Wainwright died five years to the day after he represented on the Missouri all the ordinary men and women who found uncommon courage in extraordinary circumstances to fight the impossible and endure the unimaginable for freedom from tyranny and oppression.

Or as Roosevelt said in 1942

…“sacrifice” is not exactly the proper word with which to describe this program of self-denial. When, at the end of this great struggle we shall have saved our free way of life, we shall have made no sacrifice.”

Today, it is easy to forget or diminish this “sacrifice.” However, while accepting Japan’s surrender on the deck of the Missouri, MacArthur did not. He understood that his victory rested on the Americans who persevered in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Now it is time for the U.S. Congress to go beyond MacArthur’s symbolism to recognize this critical contribution to winning the War by awarding this World War II group a Congressional Gold Medal.

Sunday, April 10, 2022

White House Proclamation

Former prisoners of war stand among the bravest of our Nation. They fought valiantly and served with honor — and under often agonizing conditions as prisoners, they demonstrated incredible personal courage, love of country, and devotion to duty. Through their extraordinary sacrifices and selflessness, they helped ensure freedom for millions of people. They are heroes.

I join all Americans in expressing our deepest gratitude to every service member who has endured being a prisoner of war and to their families, caregivers, and survivors. Their service — knowing all the risk and danger it could bring — is a credit to their character and to our Nation. On this day and every day, we remember the hardships of captivity they survived in service to our Nation. We also remember all the brave women and men who died as prisoners in foreign lands during our Nation’s past wars, and we grieve with those at home who prayed for their loved ones’ return. Their faith, love of family, and devotion to our Nation inspire us all, and we will always remember their sacrifices.

Today, our brave men and women in uniform carry on the rich legacy of our former prisoners of war — unrelenting in battle, unwavering in loyalty, unmatched in decency, and prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of our Nation.

May God bless our former prisoners of war and their families, and may God protect our troops.

NOW, THEREFORE, I, JOSEPH R. BIDEN JR., President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim April 9, 2022, as National Former Prisoner of War Recognition Day. I call upon Americans to observe this day by honoring the service and sacrifice of all former prisoners of war as our Nation expresses its eternal gratitude for their sacrifice. I also call upon Federal, State, and local government officials and organizations to observe this day with appropriate ceremonies and activities.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this eighth day of April, in the year of our Lord two thousand twenty-two, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and forty-sixth.

JOSEPH R. BIDEN JR.

Never Forget the Bataan Death March

Eighty Years Ago The horrors of today's war in Ukraine recall some of the atrocities committed by the Japanese empire during World War II.

by Mindy Kotler, proprietor the American POWs of Japan blog

Published April 9, 2022 in the National Interest

Pvt. Lester Tenney of Illinois’ 192nd Tank Battalion felt lucky. The Japanese officer’s sword missed his head and neck. Although he was left with a large gash on his shoulder, medics could quickly sew it up and he was soon back on the dusty road up the Bataan Peninsula. To fall behind or to falter guaranteed death. Like the civilians of Ukraine’s besieged cities, the surrendered soldiers and civilians on the Bataan Death March were defenseless and at the barbarous mercy of the invaders. It began eighty years ago today, on April 9, 1942.

The Bataan Death March is remembered as one of the greatest war crimes of World War II. The Japanese commanders involved were prosecuted for crimes against humanity or for violating the international laws of war and executed. So seminal in American history were these events that Bataan is part of the American lexicon as a metaphor for a tortuous undertaking. It is why National Former Prisoner of War (POW) Recognition Day is held every April 9th.

It is also one of the few Japanese war crimes for which the Japanese government has made a specific effort to atone. In 2009, the Japanese ambassador to the United States Ichiro Fujisaki, prompted by Tenney, traveled to the last convention of the American POWs of Japan and offered his country’s apology. The ambassador also arranged a visitation program to Japan for surviving POWs.

“We extend a heartfelt apology for our country having caused tremendous damage and suffering to many people, including prisoners of war, those who have undergone tragic experiences in the Bataan Peninsula, Corregidor Island, in the Philippines, and other places,” he told the men and their families.

This apology, which never appeared on the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, was repeated to four visiting delegations of American POWs by three Japanese Foreign Ministers. Japan’s current prime minister, Fumio Kishida, when serving as foreign minister, met with the 2013 POW group. Among them were two Bataan Death March survivors, including a Native American survivor, as well as two widows of Death March survivors. To his credit, he participated in the first principle of reconciliation, which is to hear their story.

The full story is that the Death March came after four months of combat starting when Japan attacked the Philippines within hours of bombing Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. A three-month siege of the Bataan Peninsula accompanied by a starvation diet, air and artillery bombardment, and disease had taken their toll. The Allies’ Europe-first policy combined with Japan’s control of the sea and air ensured that neither resupply nor reinforcement of the Philippines would come.

In the early morning hours of April 9, 1942, the newly appointed commanding general of Am-Fil forces on the Bataan Peninsula, Maj. Gen. Edward P. King Jr., realized that his troops faced slaughter if they continued to fight. He decided the rational course was to order the men and women under his command—against Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s orders—to surrender. Thus, 78,000 troops (66,000 Filipinos and 12,000 Americans) were taken captive by Imperial Japan. Among them there were dozens of European civilians—Czechs, Estonians, Latvians, Norwegians, Germans, Finns, Dutch, and British—who had volunteered to join the fight. In addition, there were at least 10,000 in two field hospitals in Bataan. It is the largest contingent of U.S. soldiers ever to surrender.

Focused on saving his exhausted and ailing troops, King could not imagine the horrors that surrender would hold. On the same day as the surrender, the Japanese put the survivors on what has become known as the Bataan Death March. It is estimated that perhaps 2,000 either swam the three shark-infested, mined miles to the fortress island of Corregidor (No one on Corregidor was on the Death March) or disappeared into the jungle. Those who made it to Corregidor became immediately members of the 4th Marines fighting shore defense. Corregidor and the associated three island fortresses surrendered on May 6th.

The Bataan Death March was a poorly commanded effort to move the surrendered troops and civilians on the peninsula to a POW camp one hundred miles north. The result was that the Japanese neglected the sick and killed the wounded; denied the POWs food, water, and medical care; and abused, robbed, and tortured them. Many men stamped into the road by tanks or shot trying to drink from a stream remain missing.

For most, the first leg of the Death March was sixty-five miles from the port of Mariveles at the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula up the East Road to a train terminal at San Fernando. Others arrived at the East Road at the village of Pilar after a sixteen-mile trek from Bagac on the west side of Bataan. It took an average of five days in the tropical heat for the terrorized, sick, and starving men to reach the station. There they were stuffed standing one hundred at a time into small, unventilated boxcars for a twenty-four-mile ride north to the town of Capas. Many died in these rolling ovens.

The survivors were forced to walk another five miles to Camp O'Donnell, an unfinished Philippine Army training camp. With only two spigots of water and no sanitation, the camp was quickly compared with the Confederacy's Andersonville prison camp. Hundreds died of disease, starvation, dehydration, and despair. Most of the deaths from the Death March happened here or at its successor camp, Cabanatuan.

Survivors of the Bataan Death March endured three-and-a-half years of death camps, brutal labor, and unimaginable indignities and injury. Many were taken to Japan aboard hellships to be slave laborers for Japanese companies in Formosa, Japan, Manchuria, and Korea. Again they were denied food, medical care, clothes, and adequate housing.

Tenney ended up in Mitsui’s Omuta coal mine near Nagasaki. The working conditions were so severe that POWs traded their meager meals to have their arm or leg broken so that they would get a short reprieve from going back underground. Today, the mine is a UNESCO World Industrial Heritage site.

More than half the Americans taken prisoner on Bataan died before war’s end. This was greater than the overall death rate for American POWs of Japan, which was 40 percent. It was more deadly to be a POW than a combat Marine in the Pacific. By comparison, the death rate for Americans taken prisoner by the Nazis was less than two percent.

As horrifying as the Bataan Death March was, it was not an exception in Japan’s war. Other death marches were imposed upon American and Allied POWs throughout the Pacific.Torture and executions were commonplace. Death from overwork and malnutrition were the norm. Abuse was systematic.

How a country treats the defenseless and dependent is a measure of their citizens’ values. How the victims endure the neglect and damage inflicted upon them also reflects values. Like the men and women on Bataan, there is much to admire in the Ukrainians. They persist and endure.

As President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in August 1943, when the outcome of World War II was still uncertain, “The story of the fighting on Bataan and Corregidor—and, indeed, everywhere in the Philippines—will be remembered so long as men continue to respect bravery, and devotion, and determination.” This still holds true eighty years later.

That Famous Photo on Bataan - No Survivors

Their hands are bound because they were found to possess either Japanese money, personal photos of Japanese, or some other contraband. The figure to the extreme right is a Japanese soldier, who the three appear to be listening to. None of the three men would survive captivity.

Samuel Stenzler was born in Tluste, Poland (then part of Austria) to a Jewish family and immigrated to the United States as a child. He married and resided in San Antonio, Texas, applying for American citizenship in 1909. Stenzler registered for the draft in World War I and was a member of the American Expeditionary Force. He returned to civilian life following the war, but after the death of his wife, he rejoined the United States Army on February 27, 1940. He was assigned to Company C, 31st Infantry Regiment of the Philippine Division, the premier American fighting unit in the Philippines. The 31st Regiment fought in the Battles of Layac (January 6, 1942) and Abucay Hacienda (January 17-24, 1942). C Company renamed the Abucay battlefield "Dead Men's Hill" because of their losses and the high number of Japanese casualties. The 31st Infantry Regiment fought a delaying action through April 1942 but was short of food, ammunition, and reinforcements throughout the campaign; the unit never had more than 60% of its authorized strength available. Company C was surrendered on April 9, 1942 with the rest of the 31st Regiment. Stenzler, 46, died at Camp O'Donnell on May 26, 1942, probably because of disease and starvation. His remains were repatriated and reburied at Long Island National Cemetery on October 18, 1949.

James M. Gallagher was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and graduated from Georgetown University in 1936. He attended Reserve Officers Training while in college. After college he joined the United States Army. When he arrived in the Philippines, he was assigned as a training officer to the 33rd Infantry Regiment of the 31st Infantry Division of the Philippine Army. Gallagher was killed the day this photo was taken or soon after. His family published a book of his letters home in memory of him. Gallagher was also honored in the annual of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. Gallagher was left off the official Prisoner of War rolls because he died on the Bataan Death March; his body was never recovered. He is also memorialized at Manila American Cemetery and Memorial. Gallagher was awarded the Silver Star, the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart.

Saturday, April 09, 2022

The Czechs on Bataan

Czechoslovak courage: Volunteerism in World War II

– Article submitted by the Embassy of the Czech Republic

April 9, 2022

In line with the Day of the Valor or Araw ng Kagitingan celebrated today, programs to honor the heroic defense and valiant fight of the men and women of war are conducted. Aside from the Filipino and American soldiers, the Embassy of the Czech Republic also pays tribute to the Czechoslovak nationals who volunteered to defend the Philippines during the Second World War.

This story of the Czechoslovak defenders of Bataan is unique, though unknown. Since they were nationals of Czechoslovakia, which at that time was under Nazi protectorate, the Japanese forces had guaranteed their safety. Nonetheless, they still chose to offer their service and therefore, were considered as the only nationals to serve in the US Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) from countries occupied by the Nazi forces. In the words of Karel Aster, one of the Czech defenders of Bataan who passed in 2019, “Fighting for the Philippines at that time was like fighting for the liberty of Czechoslovakia.”

This period in the history of the Czech Republic and the Philippines leaves an indelible mark on Czech-Philippine relations. The courageous decision to fight for the liberty of a country that was not their own was captured not only in the shrine dedicated to them in Capas, Tarlac but also in the headstones and walls of the missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial.

With more than 16,000 graves of military dead and approximately 36,000 names on the Walls of the Missing, the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial is the largest of its kind. In the vastness of its lands, measuring 152 acres, lie the immense stories of the Second World War. These stories are the subject of an educational tour hosted by the erudite guide, Vicente Paolo Lim IV.

During the visit of the members of the Embassy of the Czech Republic led by Ambassador Jana Šedivá, Mr. Lim introduced that the stronghold in Bataan from Jan. 7, 1942 to April 9, 1942 delayed the Japanese forces from advancing in the Pacific, eventually leading to Allies’ victory in World War II.

He also shared the importance of the role played by the Czechoslovak volunteers during the war. For one, they were in charge of supply and logistics, and included in their responsibilities was to retrieve the rice-milling equipment in Abucay line, exposing them to 36-hour enemy fire. This rice-mill equipment was significant in increasing the ration of food for the US forces. Thus, Jan Bžoch, Pavel (Paul) Fuchs, Leo Hermann, Fred Lenk, Otto Hirsch and Arnošt Morávek earned the American Medal of Freedom – the highest civilian distinction of the US.

Among those who volunteered, two of the graves are found at the Manila American Cemetery: Leo Hermann and Pavel (Paul) Fuchs. Each of them carried unique experiences during the war. Based on archival records, Hermann died as a prisoner of war in the Japanese concentration camp, Fukuoka, on April 2, 1945. Meanwhile, Fuchs passed in Camp O’Donnell on May 25, 1942 due to dysentery. Aside from the Czechoslovaks who volunteered for the Allied forces during the war, another grave of an American soldier of Czech origin was visited. Charles Stejskal was assigned as an infantry replacement to M Company, 172nd Infantry 43rd Infantry Division who participated in the Lingayen Gulf invasion and other subsequent operations. He was killed on Jan. 24, 1945 near the town of Rosario in Northern Luzon.

The Czechoslovak volunteers experienced various horrors in the war – from encounters with artillery fire; the infamous death march; prisoner of war camps and the hell ships where lives were lost, and in all these stories the common theme of horror and desperation is evident.

Mr. Lim is the great-grandson of a Philippine war hero, Brigadier General Vicente Lim, who heroically laid down his life for his country. For him, the dedication to tell the stories of World War II is a personal mission in order to serve as a reminder of the havoc of wars.

Similar to the story of Czechoslovak volunteers, Brig. Gen. Lim dedicated his life to defend the Philippines from foreign powers. His tactical mind and strength in strategy helped in the stronghold of Bataan. It was also in Bataan that the Czechoslovak volunteers and Brig. Gen. Lim fought together; while the Czechoslovak volunteers were dismantling and retrieving the rice mill, Brig. Gen. Lim was with the 41st Infantry Division, commanding the frontline for defence. With Mr. Lim’s personal affiliation with the story of Bataan through his great-grandfather, it has become important for him to tell the story of the past so that people will learn from it and not commit the same errors.

The visit to the cemetery was also very personal for Ambassador Šedivá. With the ongoing war in Europe when Ukraine is facing an unprovoked invasion from Russia, it is timely to remember the history and lessons of previous World Wars.

“It is important that we recall the lessons of the past – that there are no victors in wars, and civilians, especially women and children, remain to be at risk the most. While the war seems far from our door, we will all be affected in one way or another, regardless of where we are,” remarked Ambassador Šedivá.

The Czech Republic, as one of the countries that have previously been occupied by foreign invaders, remains steadfast in its commitment to remember the past and to stand for those whose liberty is challenged. In celebration of the Day of the Valor or Araw ng Kagitingan, the Embassy of the Czech Republic recalls the past and remembers those who laid down their lives for freedom.

And, in the continuing fight and worsening situation in Ukraine, it encourages the public to continue to call on all parties of the conflict to fully respect international law, and to avoid repeating the horrors of the past.

Wednesday, April 06, 2022

Remembering the Bataan Death March

In the early morning hours of April 9th, the new (March 11) commanding general of Am-Fil forces on the Bataan Peninsula, Major General Edward P. King Jr., decided that his troops would face slaughter if they tried to continue to fight. Fully aware that the 9th was the anniversary of the South's 1865 surrender at Appomattox, he ordered the men and women under his command—against General Douglas MacArthur’s orders—to surrender. Thus, 78,000 troops (66,000 Filipinos and 12,000 Americans were taken captive by Imperial Japan. Possibly 10,000 were in two field hospitals at the time. This is the largest contingent of U.S. soldiers ever to surrender.

Focused on saving his exhausted and ailing troops, General King could not imagine the horrors that surrender would hold. The same day as surrender, the Japanese put the survivors on what has become known as the Bataan Death March (BDM). It is estimated at maybe 2,000 either swam the three shark-infested, mined miles to the Fortress Island of Corregidor (NB: no one on Corregidor was on the BDM) or disappeared into the jungle. Those who made it to Corregidor became immediately members of the 4th Marines fighting shore defense. Corregidor was surrendered May 6th.

During the infamous Bataan Death March the Japanese neglected the sick and killed the wounded; denied the POWs food, water, and medical care; and abused, robbed, and tortured them. These acts were both capricious and systematic. They became a constant for every POW of Imperial Japan. Thousands died. The first leg of the BDM March was 65 miles from the port of Mariveles at the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula up the East Road to a train terminal at San Fernando. There the men were stuffed standing one hundred at a time into unventilated box cars for a 24 mile ride north to Capas. There the survivors--many died standing--were forced to walk another four miles to an unfinished Philippine Army training camp that was Japan's first POW camp on the Islands, Camp O'Donnell. With only two spigots for water, the camp was quickly compared with the Confederacy's Andersonville prison camp. Most of the deaths from the March happened here or at its successor camp Cabanatuan.

Survivors of the March endured three and a half years of death camps, brutal labor, and unimaginable indignities and injury. Many were taken to Japan aboard hell ships to be slave laborers for Japanese companies. More than half the Americans taken prisoner on Bataan died before war’s end. The death rate for American POWs of Japan was 40%, whereas for those in Nazi POW camps it was less than 2%.

If you want your congressperson or two senators to remember this eventful day, I urge you to contact them immediately and ask why they are going into recess on Thursday without offering any statements or attending any memorial events. A Tweet will not do. Here is American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Memorial Society Jan Thompson' s testimony last month to the House and Senate Veterans Committees., https://www.veterans.senate.

If you want your congressperson or two senators to remember this eventful day, I urge you to contact them immediately and ask why they are going into recess on Thursday without offering any statements or attending any memorial events. A Tweet will not do. Here is American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Memorial Society Jan Thompson' s testimony last month to the House and Senate Veterans Committees., https://www.veterans.senate. The Japanese have not forgotten. They arranged and have leaked the fact that the Speaker of the House of Representatives and a large delegation of members of congress will meet with the Japanese PM in Tokyo on April 9th.

The Japanese have not forgotten. They arranged and have leaked the fact that the Speaker of the House of Representatives and a large delegation of members of congress will meet with the Japanese PM in Tokyo on April 9th.If you want to participate in a memorial event, here is a list of what I could find.

1. FRIDAY, APRIL 8, 11:00 am. World War II Memorial, Washington, DC.

Hosted by The Philippine Embassy

Annual ceremony at the National WWII Memorial by the Pacific Victory Arch at the Southern Fountain Coping by the engravings of the words “Bataan” and “Corregidor”

https://www.nps.gov/wwii/

https://www.

The Philippine Ambassador and Filipino military officials attend. Helping organize the event is Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project (FilVetREP) that is headed by General Tony Taguba, who is best known for his investigation of the war crimes at Abu Ghraib prison.

On April 2nd, FilVetsREPs hosted a memorial walk/run at The Marina on Daingerfield Island in Alexandria, Virginia.

Contact: Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project

5002 Halley Farm Ct.

Alexandria, VA 22309

2. SUNDAY, APRIL 10, 11:30 am, USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum Alameda, CA.

Hosted by Bataan Legacy Historical Society, the Philippine Scouts Heritage Society and the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor Memorial Society

Remembrance and Reconciliation, Bataan Death March 80th and honoring those on the three ship hellship voyage to Japan from December 1944 to January 1945. Planes from the USS Hornet bombed two of the ships, killing over 600 POWs. These men included Amb Walter Mondale's first cousin and the Smothers Brothers' father. Of the 1,600 men who boarded the Oryoku Maru in Manila on December 13, 1944, less than 300 survived the war. The event is organized by the Filipino American organization, Bataan Legacy Historical Society.

>Governor Gavin Newsom has been invited. His maternal grandfather Arthur Menzies was with 60th Coast Artillery Regiment on Corregidor. He was a POW who was taken by hellship to Japan where he was a slave laborer for Nippon Steel mining coal. Menzies committed sucide in front of his twin daughters in 1973 when Newsom was 6.

Contact: Cecilia I. Gaerlan, Executive Director,

Bataan Legacy History Society

(510) 520-8540, cecilia@bataanlegacy.org

http://www.bataanlegacy.org/

3. SATURDAY, APRIL 9, 1:00pm Symbolic March, 2:00 pm Program, Dominican College, Orangeburg, NY

Hosted by the Philippine American Cultural Foundation

Remember Bataan. Symbolic March on Bataan Road at the site of the former Fort Shanks, followed by a formal program at Dominican College.

Gathering for March at 12:30pm at Tappan Zee High School, Dutch Hill Rd., Orangeburg, NY,

Program at Dominican College, Hennessy Center, 495 Western Hwy S, Blauvelt, NY 10913

Camp Shanks was built when the story of Bataan was still fresh in everyone’s memory. Two intersecting streets at the camp were named Bataan Road and Victory Road. This was to remind the troops departing for Europe that if they could emulate the courage, fortitude and spirit of men on Bataan and Corregidor victory would be achieved.

Contact: Jerome Kleiman, Executive Director

Philippine American Cultural Foundation

(845) 641-4217

4. MARCH 20th – 27th. White Sands, New Mexico

Hosted by the White Sands Missile Range and the New Mexico National Guard

Annual Memorial Death March organized since 1989

The past two years has been held as a virtual only event.

The March has grown from 100 to almost 10,000 in the last in-person event.A number of Senators would join.

Contact: White Sands Missile Range Public Affairs Office

FMWR-Bataan P.O. Box 400

White Sands Missile Range, NM 88002

usarmy.wsmr.atec.list.pao@

5. SATURDAY, APRIL 2, 2022, Noon (Closing Ceremony), Chesapeake, Virginia

Hosted by the VFW, SSG Jonathan Kilian Dozier Memorial Post 2894

Annual Bataan Death March Memorial Walk held at the Dismal Swamp Canal Trail,

1113 George Washington Hwy, Chesapeake, VA 23323

The event consists of three different walks starting at 7:00 am of various distances as well as a memorial ceremony dedicated to the survivors and other veterans. The event is open to all.

https://walkchesapeake.

Contact: LTC Carl M. Dozier, AUS, Ret. Gold Star Father, bulldoziero5@gmail.com,

VFW Post 2894 commander or

Jose Vazquez, (757) 362-4227, jose@latinopridestore.com or walk.chesapeake@gmail.com

6. SATURDAY, APRIL 9, 10:00 am, Wreath Laying Ceremony, Brainerd, Minnesota

Hosted by the Brainerd National Guard 1st Combined Arms Battalion, 194th Armor Regiment

Annual ceremony at the Brainerd Training and Community Center (National Guard Armory), 1115 Wright St., Brainerd, MN 56401

The ceremony be livestreamed on the following Facebook pages: https://www.facebook.com/

https://www.facebook.com/

On September 22nd there is a Memorial Death March run.

Contact: (651) 268-8113, 194regiment@gmail.com

Event contacts: Capt Michael Popp, (651) 268-8681

Sgt First Class Jade Caponi, (651) 268-8123, jade.a.caponi.mil@army.mil

Battalion Commander, Lt Col Jacob Hegestad

7. SATURDAY, APRIL 9, 10:00 am - 4:00 pm, Rededication of Bataan Memorial Park, Fort Bayard, New Mexico

Hosted by several community organizations

Annual festival and commemoration. This year’s event will take place between 10:00 am and 4:00 pm. https://www.

https://www.facebook.com/

Contact: Ms. Liz Lopez, (575) 574-2964, egarcia3264@gmail.com

8. SATURDAY, APRIL 9, 6:00 am, Bataan Death March Commemoration

Valdosta, Georgia

Hosted by Lowndes County Sheriff’s Office

First held in 2021. The course is broken up into three legs, each 8.7 miles long, Marchers can cover one or two legs or complete the whole course.

Contact: Lt Rob Picciotti, lcsobdmt2022@gmail.com with the subject line “BATAAN MARCH.” $20 fee.

9. INDEFINITELY POSTPONED, Bataan Memorial Park, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Honoring New Mexico's 200th and 515th Coast Artillery men, defenders of Luzon, Bataan and Corregidor

https://www.krqe.com/

https://www.cabq.gov/

Contact: (505) 226-4899, bataan.nm@gmail.com

10. SATURDAY, MAY 7, 10:00am-Noon, Bataan & Corregidor Commemoration

Hosted by the ADBC Museum, Education & Research Center, Wellsburg, West Virginia

Memorial service followed by lunch at the ADBC Museum, Education & Research Center,

Contact: Mr. James S. Brockman, Curator

945 Main Street, Wellsburg, WV 26070, (304) 737-7295, jim.brockman@wvlc.lib.wv.us

11. SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2022. Maywood Bataan Day, Maywood, Illinois

Maywood Bataan Day Organization

Every Third Sunday in September. Begun in 1942, by the American Bataan Clan (ABC)m it is the oldest continual ceremony honoring the men of Company B, 192nd Tank Battalion who fought on Bataan. The town had the greatest number of soldiers from one town on the Bataan Death March.

One of the featured speakers at the first rally was Illinois Governor Green (1941 – 1949), who remarked, “…the heroism of the men who defended Bataan and Corregidor and our other outposts will endure forever, giving new inspiration and new courage to free men everywhere”.

Contact: Col Richard A Mcmahon, Jr., President, ramcmahon1@aol.com